November 28, 2025

Introduction

Cyber charter school funding in Pennsylvania is out of control. Earlier this year, Auditor General Tim DeFoor released a report finding that the state’s five largest cyber charter schools have rapidly accrued hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars in reserves.[1] This practice, though legal, has been paired with questionable spending habits by cyber charters, whose enrollment has skyrocketed during the pandemic. At the same time, public schools face fiscal stress, and K-12 education remains highly underfunded and inequitable in Pennsylvania.

Charter schools are taxpayer-funded but more autonomous than traditional public schools. If a family is dissatisfied with their child’s education in their local public school, the public school must pay to send that student to a charter school, which can either be brick-and-mortar or cyber. Cyber charters can be entirely online or incorporate some face-to-face instruction, and students learn through live instruction from teachers and independent work.

Enrollment in Pennsylvania’s 14 cyber charters has skyrocketed since the pandemic, growing 60 percent between the 2019-20 and 2022-23 school years.[2] With this uptick have come increasing calls for reform in Harrisburg. Governor Shapiro’s 2025 budget, which passed in November after a 134-day impasse, includes a slate of reforms to enhance accountability and ease the financial burden on public schools.[3] However, the budget comes short of tackling a more systemic challenge: adjusting a lopsided funding formula that over-allocates tuition money to cyber charters, siphoning millions in vital funding from public schools.

Cyber Charter School Funding

Public school funding is the direct source of revenue for cyber charters. Pennsylvania’s five largest charter schools more than doubled their reserves between 2020 and 2023, holding a combined $619 million in taxpayer funds in reserve as of June 2023.[4] Reserves are necessary to cover unanticipated expenses and ensure the continuity in every student’s education. However, the combined reserves of these top cyber charters grew nearly 10 times faster than those of traditional school districts in just the 2020-21 school year.[5]

Why are cyber charters’ reserves growing so quickly? It has to do with more than rapidly increasing revenues. In Pennsylvania, the decades-old Charter School Law sets tuition rates, or the standard annual payment that public school districts must send to charter schools to fund the education of each child. Pennsylvania uses a tuition formula for both cyber and brick-and-mortar charters based on each public school district’s per pupil budgeted expenditure.[6]

Because there are 500 public school districts in Pennsylvania, and because each district has a different cyber charter tuition calculation for regular and special education students, there are currently 1,000 different rates paid to the same statewide charter schools.[7]

The formula also means the amount of money that public school districts send cyber charter schools for each student is entirely disconnected from the actual cost of providing a virtual education for that student. The formula incorporates deductions for certain costs that cyber charters do not incur compared to districts or that are offset by other sources, lowering the amount allocated to charters.[8] But in most cases, districts can educate a student in a cyber program for less than $8,000 (the amount of Governor Shapiro’s proposed cyber charter tuition cap).[9]

For instance, a cyber charter may receive $12,000 to educate a student, but because they do not maintain physical facilities or offer holistic services like counseling or extracurriculars, their actual annual per pupil expenditure may only be $8,000—leaving the extra sum to be spent on other costs or put into reserves. In addition to amassing reserves through this distorted formula, large cyber charters have been found to spend taxpayer money on items unrelated to education. According to DeFoor’s audit, cyber charters have spent millions on gift cards to students and families, staff bonuses, and the purchase and renovation of physical facilities.[10]

Further, the five cyber charters investigated spent over $28 million during the audit period on advertising, $21.7 million of which was spent by the Commonwealth Charter Academy (CCA), the state’s largest cyber charter.[11] CCA buys airtime on radio and television programs and advertises with billboards, buses, transit shelters, and social media—all to convince parents to send their children to CCA, further increasing revenues. School districts also spend money on advertising (oftentimes on state requirements, such as posting public notice of board meetings and soliciting bids from contractors), but it is significantly less. In 2023–24, CCA alone spent $8.7 million on advertising—more than the advertising spending of 474 school districts combined.[12]

The five largest cyber charters also spent nearly $1.4 million on lobbying during the audit period.[13]

Public school districts lose money each time a student leaves to attend a charter school because the district is legally required to pay the charter school tuition for that student. Cyber charter schools spend some of that money on marketing to recruit even more students; so, districts are effectively financing the efforts that encourage families to leave their schools. As more students leave, districts send even more money out the door, which makes it harder to maintain programs, staff, and resources. In other words, under Pennsylvania’s current law, districts are required to fund the entities that accelerate their decline.

Implications for Public School Districts

The rise of cyber charters has driven the heightened fiscal stress that Pennsylvania school districts have suffered in recent years. Districts have cited mandatory charter school payments as the top source of budget pressure for six consecutive years.[14] One school district official writes, “Cyber charter costs continue to be exorbitant and an albatross financially for our district.”[15]

Source: PASBO

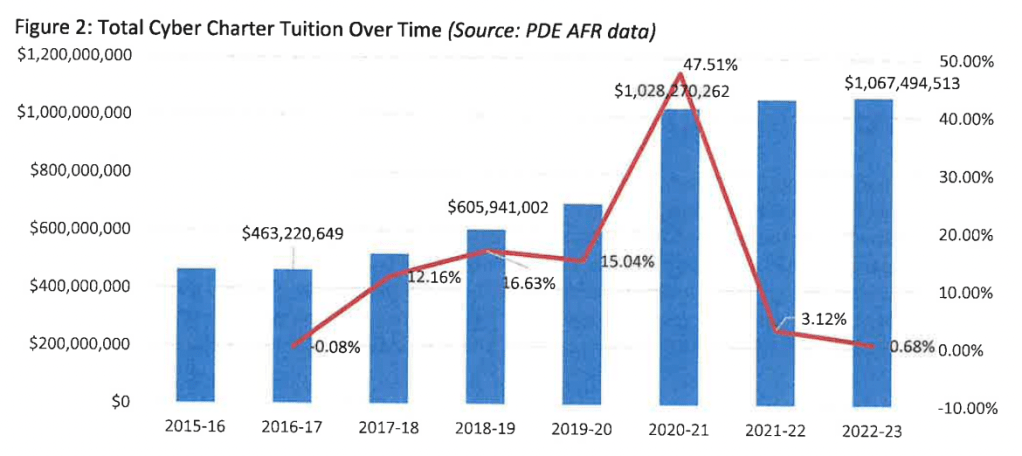

Between the 2015-16 and 2022-23 school years, cyber charter tuition costs for school districts rose by nearly 14 percent each year.[16] The Greater Johnstown School District paid under $10,000 in cyber charter tuition in 2001-02; by 2023-24, the annual expenditure had ballooned to $4 million and doubled to nearly $8 million the very next year.[17] In Allegheny County, 7 percent of Woodland Hills School District’s expenses are cyber charter tuition payments—what amounts to essentially a reduction in its budget.[18] Further, small (oftentimes rural) school districts are hit the hardest, as their per pupil operating costs are higher, which means more paid to cyber charters when students leave.[19]

The broken funding formula means that as costs increase for school districts, they are mandated to pay more and more towards charter school tuition. Recall that the tuition formula is based on each school district’s operating costs—so, as costs increase each year (because of other mandated costs as well, including teacher pension payments), the cyber charter tuition rates increase, meaning that public school districts pay out more and more. This creates a cost feedback loop in which cyber charter tuition only goes up.[20] The funding drain from public schools will drive more students out of their districts in search of better education, further weakening the public school system.

The formula also means that recent state investments in equity drive up cyber charter tuition, nullifying the intended benefits. Lawmakers allocated $500 million in last year’s state budget to strengthen K-12 public education, a portion of which, labelled “adequacy funds” went to 348 of the state’s 500 school districts to address educational disparities.[21] As the Pennsylvania Association of School Business Officials (PASBO) writes, “a portion of all of these new funds to school districts will immediately flow out of school districts and into cyber charter tuition each year.”[22]

The investment was partially—or in some school districts, entirely—negated by cyber charter payments. PASBO notes that in over 200 school districts, proposed net increases in state funding for school districts from this year’s state budget are entirely zeroed out if fewer than ten students move to a cyber charter, taking tuition payments with them.[23] 73 school districts reported that they are using these increased state funds to directly offset charter tuition costs; Penn Hills reports that all $860,000 of its adequacy funding is being used for this purpose.[24]

Pennsylvania’s school funding system is so inequitable it has been deemed unconstitutional, and it remains one of the poorest performing states in K-12 educational equity.[25] State lawmakers must continue to reduce educational disparities between school districts. But because of the broken cyber charter formula, much of the progress potentially gained from the hundreds of millions that lawmakers pour into closing gaps between rich and poor districts is immediately being undone. Cyber charter funding reform should be treated as what it is: a major equity concern.

Cyber Charter School Performance

Support for charter schools comes as part of a growing “school choice” movement, which is underpinned by economist Milton Friedman’s argument that increased privatization of public education will promote competition, creating top-performing schools.[26] Cyber charters certainly provide an option for students whose circumstances create obstacles to education in a regular classroom, and parents cite flexibility, medical or mental health concerns, and school safety as reasons for enrolling.[27] However, cyber charters consistently produce subpar student achievement.

Cyber charter students show considerably lower proficiency on standardized tests, with just 10 percent of Algebra 1 students scoring “proficient” or “average” on state exams, compared to the statewide average of 40 percent.[28] This translates to learning loss. Cyber charter students experience the equivalent of 106 fewer days of learning in reading and 118 fewer days of learning in math compared to similar peers in traditional public schools; achievement gaps are even greater between cyber and brick-and-mortar charter students.[29] Every additional year at a cyber charter school also increases the probability of chronic absenteeism and decreases the probability of enrolling in post-secondary education.[30] The four-year graduation rate for cyber charters in Pennsylvania averages 65 percent, while the statewide average is 87 percent.[31]

Proposed Reforms

Pennsylvania’s 2025-26 budget includes a number of reforms for cyber charters, including greater accountability around student attendance, residency, and wellness. The funding formula has been slightly modified to enable school districts to remove cyber charter tuition expenses and the number of cyber charter students in their tuition calculations, functionally decreasing tuition rates. Lawmakers claim this will return $178 million to school districts. Cyber charters claim that the reduction in their revenue will be closer to $300 million and will force a handful of cyber charters to go out of business.[32]

This budget is a far cry from Governor Shapiro’s initial proposal, which would have set a flat base cyber charter tuition rate of $8,000 per student per year, estimated to save school districts $378 million annually.[33] This year’s compromise reforms replace last year’s one-time set of reimbursements to school districts that totalled $100 million to offset cyber charter tuition costs.[34]

The final law imposes needed accountability standards and temporarily eases the financial burden on school districts, and by deducting cyber charter expenses from the tuition rate formula, it eliminates the cost feedback loop that was continually driving payments up. But it is only a bandaid on a much deeper problem. Cyber charter tuition is still not linked to the actual cost of providing a virtual education.

When cyber charters grow, they do so directly at the expense of public school districts. A willingness from lawmakers to commit to true reforms—a fully adjusted formula or tuition cap—would signal a commitment to protect public education while it is under threat by ensuring balanced, stable, and adequate funding and the responsible spending of taxpayer dollars.

Image Credits: Michael Rubinkam / The Associated Press. https://www.witf.org/2022/07/27/what-kind-of-education-does-pa-owe-its-public-school-students-a-judge-will-now-decide/

Endnotes

[1] Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of the Auditor General, Performance Audit Report: Commonwealth Charter Academy, Pennsylvania Leadership Charter School, Insight PA Cyber Charter School, Pennsylvania Cyber Charter School, Reach Cyber Charter School, Timothy DeFoor. Harrisburg: 2025, https://paauditor.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/speCyberCharters022025.pdf.

[2] Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of the Auditor General, Performance Audit Report, Commonwealth Charter Academy, 3.

[3] Peter Greene, “Pennsylvania Budget Cuts Cyber Charter Funding, Adds Accountability,” Forbes, November 13, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/petergreene/2025/11/13/pennsylvania-budget-cuts-cyber-charter-funding-adds-accountability/.

[4] PA Dept. of the Auditor General, Performance Audit Report, Commonwealth Charter Academy, 2–3.

[5] Jillian Forstadt, “Cyber Charter Reform Could Save Some Southwestern Pa. Schools More than $1M,” 90.5 WESA, February 28, 2024, https://www.wesa.fm/education/2024-02-28/cyber-charter-reform-pennsylvania.

[6] “PASBO Testimony to the House Education Committee: Cyber Charter School Funding,” Pennsylvania Association of School Business Officials, May 2, 2025, https://www.pahouse.com/files/Documents/Testimony/2025-05-01_023609__Cyber%20Charter%20School%20Costs%20Hearing%20Testimony.pdf, 3–4.

[7] “PASBO Testimony: Cyber Charter School Funding,” 9.

[8] PA Dept. of the Auditor General, Performance Audit Report, Commonwealth Charter Academy, 3.

[9] “PASBO Testimony: Cyber Charter School Funding,” 4.

[10] Personal correspondence with an intermediate unit employee, 2025.

[11] PA Dept. of the Auditor General, Performance Audit Report, Commonwealth Charter Academy, 38.

[12] Derived from AFR data found on the PA Dept. of Education website, https://www.pa.gov/agencies/education/programs-and-services/schools/grants-and-funding/school-finances/financial-data/summary-of-annual-financial-report-data/afr-data-detailed.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “2025 State of Education Survey,” Pennsylvania School Boards Association, https://www.psba.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/State_of_Education_Report.pdf, 23.

[15] Ibid. 34.

[16] “PASBO Testimony: Cyber Charter School Funding,” 2.

[17] “Testimony to the House Education Committee: Mr. Michael Dadey, Asst. to the Superintendent, Johnstown School District,” 1.

[18] Forstadt, “Cyber Charter Reform.”

[19] Kate Huangpu, “Costly cyber charter tuition is consuming tens of millions of new state dollars for poor Pa. schools,” May 3, 2025, https://www.wesa.fm/education/2025-05-03/cyber-charter-tuition-pennsylvania.

[20] “PASBO Testimony: Cyber Charter School Funding,” 6.

[21] Huangpu, “Costly cyber charter tuition.”

[22] “PASBO Testimony: Cyber Charter School Funding,” 7.

[23] “PASBO Testimony: Cyber Charter School Funding,” 3.

[24] Huangpu, “Costly cyber charter tuition.”

[25] Aubri Juhasz, “Judge deems Pennsylvania’s school funding system unconstitutional,” 90.5 WESA, February 7, 2023, https://www.wesa.fm/education/2023-02-07/judge-deems-pennsylvanias-school-funding-system-unconstitutional?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=17812104892&gbraid=0AAAAADLgYd56Z7PrxPEYZuZRgQyv0oSUC&gclid=CjwKCAiAz_DIBhBJEiwAVH2XwP_H9c7qZyp0qElP08XQq0UOQCHLWP4qP7i_g6MozW_haidkHTzcVhoCxFkQAvD_BwE.

“Rankings of the States 2019 and Estimates of School Statistics 2020 NEA Research,” 2020, https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/2020%20Rankings%20and%20Estimates%20Report%20FINAL_0.pdf.

[26] Milton Friedman, “The Role of Government in Education,” in Economics and Public Interest, ed. Robert Solo (Rutgers University Press, 1955), 123–144.

[27] Oliver Morrison, “Why Parents Are Sending Kids to Pa.’s Fastest-Growing Cyber Charter,” Center for Digital Education, October 13, 2025, https://www.govtech.com/education/k-12/why-parents-are-sending-kids-to-pa-s-fastest-growing-cyber-charter.

[28] Katie Meyer, “The Shapiro admin will consider whether an ‘AI-driven’ cyber charter school can operate in Pa.,” 90.5 WESA, January 25, 2020, https://www.wesa.fm/education/2025-01-25/pennsylvania-josh-shapiro-ai-cyber-charters.

[29] “Charter School Performance in Pennsylvania,” Center for Research on Education Outcomes (Stanford University), 2019, https://credo.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2019_pa_state_report_final_06052019.pdf, 39.

[30] “The Effects of Charter Schools on Student Outcomes in Pennsylvania,” College of Education, Temple University, June 2019, https://www.pa.gov/content/dam/copapwp-pagov/en/education/documents/data-and-reporting/research-and-evaluation/pa%20-%20the%20effects%20of%20charter%20schools%20on%20student%20outcomes%20in%20pennsylvania%20-%20full%20report.pdf, 16.

[31] “Testimony to the House Education Committee: Dr. Sherri Smith, Executive Director, Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators,” April 25, 2025, https://www.pahouse.com/files/Documents/Testimony/2025-04-25_073604__2025-04-25%20Cyber%20Charter%20Outcomes.pdf, 5.

[32] Greene, “Pennsylvania Budget Cuts Cyber Charter Funding.”

[33] “Governor Shapiro’s Budget,” https://www.pa.gov/governor/governor-shapiro-s-budget.

[34] “PASBO Testimony: Cyber Charter School Funding,” 10.